David Haygood– I grew up here. I met my wife here. I got married here. And, eventually, I was hoping one day to be buried here, but that won’t happen.

Karen Dixon – I had always hoped that we could hold on to the property. It felt as though we needed to move, because, one, we were landlocked. You couldn’t have a funeral during the day, because we had no place for parking. The church itself only owned eleven parking spaces that are directly behind the church. And, so, we I think had known for a long time that we would have to move somewhere. And, we lacked community to pull in.

David Haygood– From a logical standpoint, I knew we had to move. I knew. I knew it. But, this building meant so much to me. It meant a lot to me and my family and these people. We just didn’t want to leave it.

Clara Lewis – I was hurt. I felt like I had lost everything that I had really gained and learned. I knew that the people – we were not going to have the people. We were not going to see them, because we would see them during the week. Because, we had meetings here. We came here. We had gatherings here. We had receptions here. We had weddings here. We couldn’t have anything here anymore. My daughter, actually, was the last one to get married here, and that was like fifteen years ago this October.

James McClellan – Why did we survive urban renewal? By the grace of God, and that’s the real answer. There was a reason for Grace to still stand here and to be a representation of what this neighborhood was.

Karen Dixon – We were one of the last vestiges of Brooklyn that was left here. And, I think that probably, in a lot of ways, we almost felt like we had to be the holder of the history. And, with us being here, I think a lot of our struggle was: “Well, we gotta stay, because, you know, we’re all that’s left.”

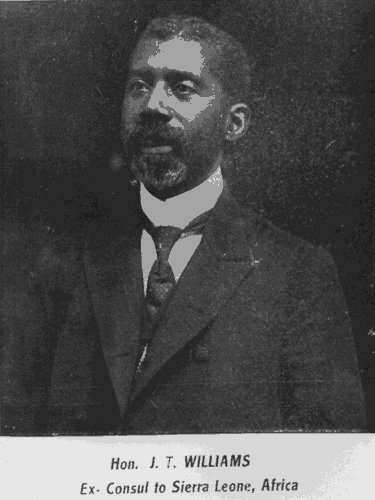

John Taylor Williams

J. T. Williams was born May 1, 1859, in Cumberland County, North Carolina, to free African Americans, Peter Williams and Flora Ann McKay. His parents made sure he obtained an education at an early age. In 1876, Williams enrolled at the State Normal School in Fayetteville (now Fayetteville State University) and graduated as valedictorian of his class in 1880. Upon graduation, he taught school for three years in several towns across the state, including Charlotte.

In 1883, Williams left the teaching profession, entered Leonard Medical School in Raleigh, and graduated in 1886. After receiving his state medical license, he set up a practice in Charlotte and became one of the first three African Americans to practice medicine in North Carolina.

Williams entered politics in 1889 and was elected to the board of aldermen (now city council) for two consecutive terms. In 1892, Williams co-founded the Queen City Drug Company, which grew into one of Charlotte’s most successful Black businesses. Like other prominent African Americans in the city, Williams accumulated wealth by investing in real estate and farming endeavors.

In 1897, President William McKinley appointed him as the U.S. consul to Sierra Leone, which he held until 1906. Upon his return, Williams continued to invest in real estate and other financial ventures, like the Afro-American Mutual Insurance Company (1907). In 1917, he helped form Charlotte’s Colored Chamber of Commerce and the Mecklenburg Investment Company (1922). Williams died in 1924.

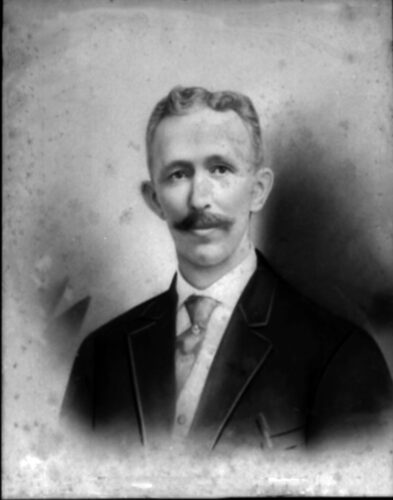

Thaddeus Lincoln Tate

Thad Tate was born October 26, 1865, in Morganton, North Carolina, to Thaddeus Tate, Sr., and Maggie Kinson. After his father died in 1877, he moved to Charlotte with his mother, who shortly afterward remarried. Tate was introduced to the barbering trade by his stepfather, James Pethel. By 1890, Tate opened his own barbershop in the center of the city at Trade and Tryon in the Central Hotel. He operated this barbershop for nineteen years before relocating to South Tryon and 4th Street in 1909.

Tate accumulated wealth by investing in stock in a local building and loan association and quickly became a pillar in both the African American and larger Charlotte business communities. He was instrumental in helping found several important Black institutions in the city, including Grace A.M.E. Zion Church (1902), Brevard Street Library (1903), Afro-American Mutual Insurance Company (1907), and the Mecklenburg Investment Company (1922). Tate died in 1951.

Caesar Blake, Sr.

Caesar Blake, Sr. was born March 2, 1861, in Winnsboro, South Carolina. He married Minnie Mendenhall in 1883. In 1891, he secured a job in the Railway Mail Service (RMS), and in 1895 he relocated his family to Charlotte to work on the Charlotte, NC to Augusta, GA. railway mail route.Blake purchased a home at 425 E. First Street and became a founding member of the board of trustees at Grace A.M.E. Zion. The official nature and mobility of his job made him a respected member of Charlotte’s Black community. However, railway mail clerks of his era faced many dangers, because the wooden mail cars on which they were forced to work were located behind the steam engine. Blacks mostly held these positions because whites refused to endure the safety hazards of scalding steam, explosive boilers, and collisions in outdated wooden mail cars.

In the early 1910s, when the US Postal Service began replacing the wooden cars with steel cars, African American railway mail clerks, barred from white federal labor unions, were forced to organize their own labor union to protect their now desirable jobs. Blake is credited with being instrumental in helping the National Alliance of Postal Employees establish union locals throughout North Carolina. After thirty-eight years of employment, he retired from the RMS in 1929. Blake died in 1940.

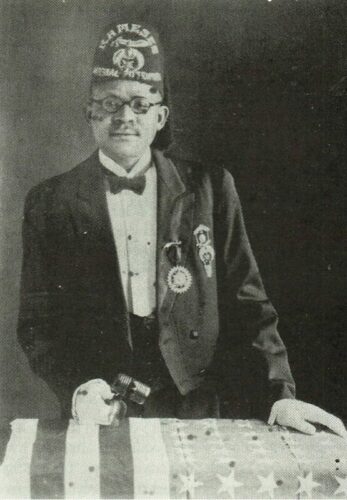

Caesar R. Blake, Jr.

Caesar R. Blake, Jr. was born December 24, 1886, in Longtown, South Carolina. He was the third child born to Caesar Blake and Minnie Mendenhall. Blake moved with his family to Charlotte in 1891 and attended the city’s public schools and Biddle University (now Johnson C. Smith University).

Following graduation, in 1905, he secured a position in the Railway Mail Service and began investing in real estate and insurance endeavors. Blake also became deeply involved in the Black fraternal order world. In 1919, he was elected as national leader or Imperial Potentate of the Prince Hall Shriners, and in 1922 he helped found the Mecklenburg Investment Company. At the time, white parallel fraternal orders were seeking to prevent African Americans from using the same names, symbols, and rituals associated with white Shriners, Elks, and Odd Fellows.

William W. Smith

William W. Smith was born in 1862, in Mecklenburg County. At an early age he married Keziah E. Eggston, a native of South Carolina. As a young man, Smith apprenticed with William H. Houser, a local African American brick mason, builder, and owner of a brickmaking operation in Uptown Charlotte’s Brooklyn neighborhood.

This work helped Smith launch his own career as a brick mason, building contractor and designer; he came to be regarded as Charlotte’s first Black architect. Smith played a central role in Charlotte’s Black business renaissance of the early 20th century. He built his most recognized works along South Brevard Street and on the Livingstone College campus in Salisbury. He not only constructed Grace A.M.E. Zion Church, but he also built the Mecklenburg Investment Company, Brevard Street Library, A.M.E. Zion Publishing House, the Afro-American Insurance Company buildings in Charlotte and Rock Hill, and the Hood Theological Building and Goler Hall at Livingstone College in Salisbury. Smith lived at 409 South Caldwell Street. He died on May 23, 1937.

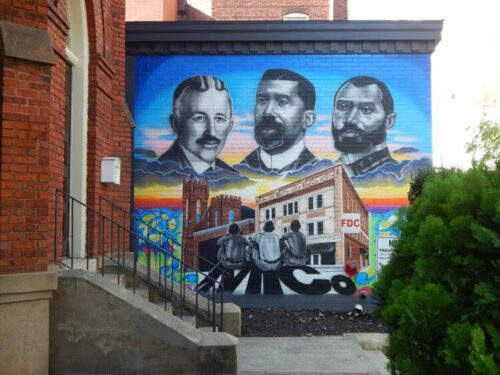

MIC Mural

Painted by local artist Abel Jackson, the MIC mural honors the memory of Brooklyn and features the likenesses of Thad Tate, J. T. Williams, and W. C. Smith (L to R).

Abel shared the following thoughts on the mural and Brooklyn:

“One of the best things I can ask for as an artist is to participate in a creative project where I have the chance to learn more about our history and myself. I am very grateful for the opportunity to paint a mural that commemorates the legacy of Brooklyn, 2nd ward, in Charlotte Mecklenburg. In the community of Brooklyn, “A city within a city” there were great educators, entrepreneurs, and civic leaders who pulled their resources together in order to help uplift their community. The things they were able to accomplish show and prove our greatness and what can happen when we work together.”

The Brooklyn Collective

The Brooklyn Collective is a Charlotte-based non-profit promoting

inclusivity and economic mobility. They are housed in the historic Grace AME Zion Church and the Mecklenburg Investment Company buildings on S. Brevard Street.