Despite Brooklyn’s prosperity, poverty, health concerns, and crime were the things that made the headlines. City officials labeled Brooklyn as “blighted” and called for its destruction in the 1950s. For years absentee white landlords brought in profits while their properties deteriorated. Local media outlets highlighted the impoverished and rougher areas of the community like Blue Haven and “Murder Corner” which portrayed the neighborhood as a dangerous community just outside Charlotte’s main business district.

White-collar workers commuting from Myers Park, and other affluent white suburbs had to drive by Brooklyn on their way to and from work in Uptown. By 1957, city officials labeled Brooklyn as an “eyesore” that they had to do something about it. The city’s white leaders pursued urban renewal with three main goals: clearing the so-called “slum,” relocating residents with better housing elsewhere, and redeveloping the area to increase property tax revenue.

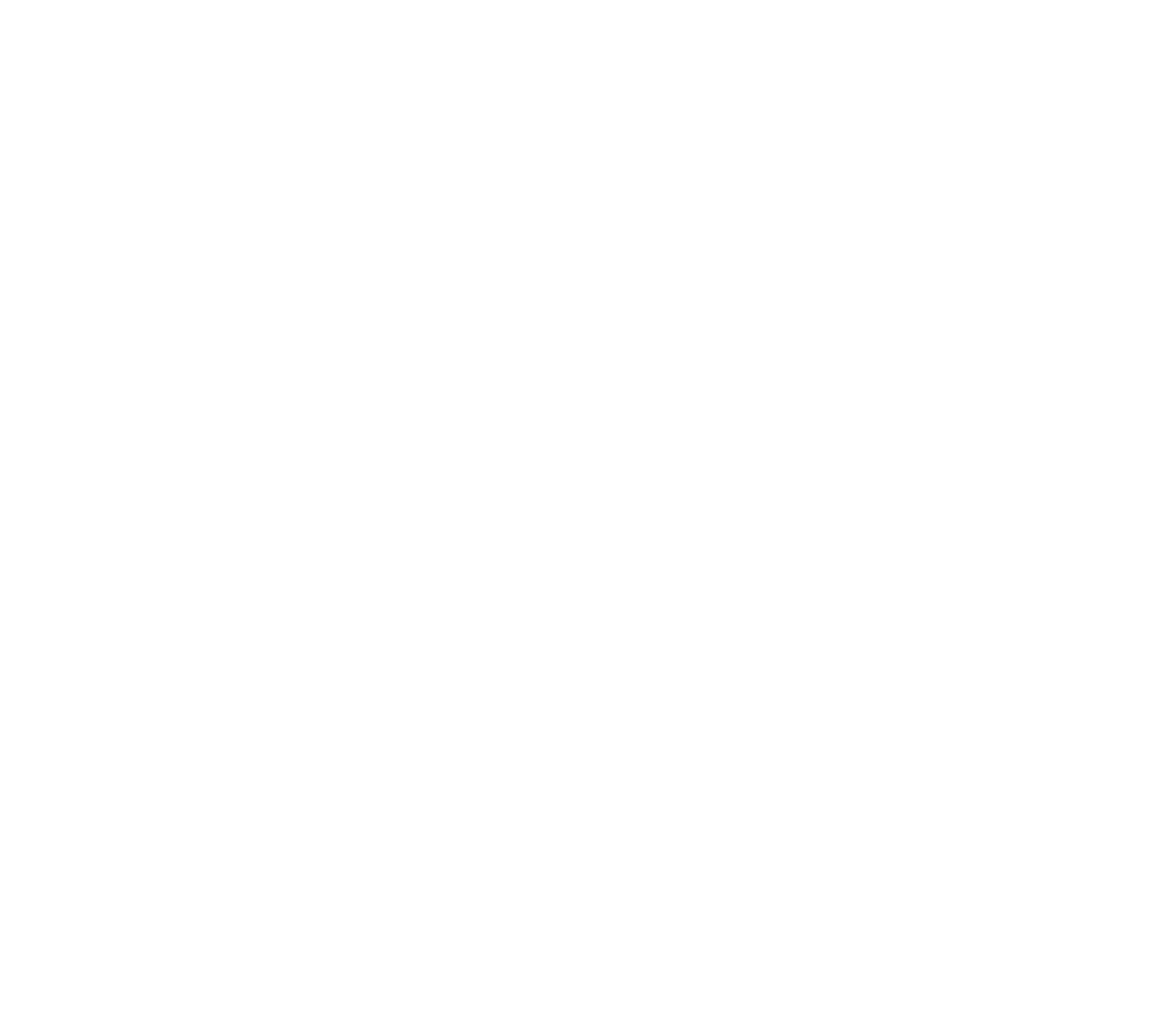

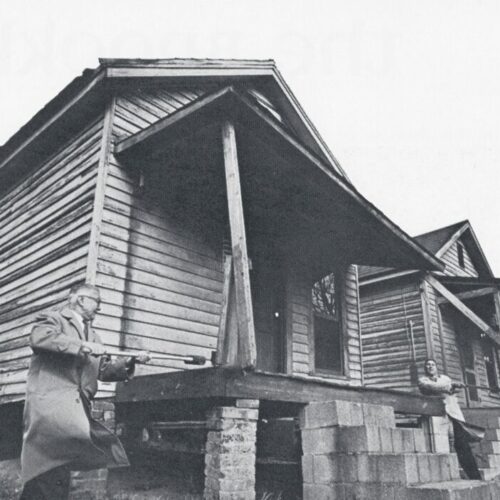

Protests emerged immediately, especially from the NAACP and other groups who feared the displacement of Brooklyn’s poorest residents without new public housing. Nevertheless, the city moved forward. In June 1958, the federal government approved Charlotte’s first of several urban renewal project applications. Charlotte’s Redevelopment Commission Director Vernon Sawyer outlined a five-phase plan to demolish Brooklyn. On December 20, 1961, Mayor Stan Brookshire took the first sledgehammer to a Brooklyn residence.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, city leaders used federal urban renewal funds to change the face of Uptown Charlotte at the cost of dismantling Black communities in Brooklyn other areas like First and Third Wards, Greenville, and Dilworth. While new expressways and interstates severed communities like Lincoln Heights, McCrorey Heights, and Biddleville in West Charlotte.