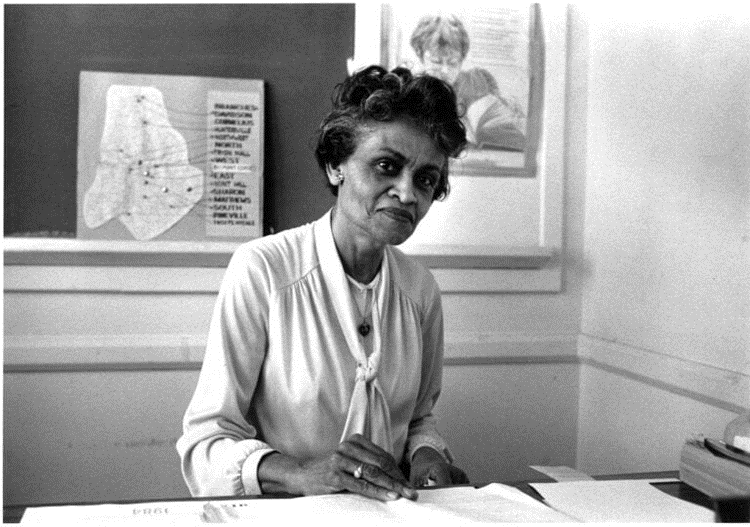

Allegra Westbrooks

In this interview, Allegra Westbrooks shares her interest in books at a young age and her campaign to “spread the gospel of books and reading.”

This recording is an excerpt from the Allegra Westbrooks oral history interview, 2007 March 12, J. Murrey Atkins Library Special Collections and University Archives, University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Transcript: Well, as a child growing up in Fayetteville, North Carolina, I used to peek in the window of the all-white public library, and then dart away before getting caught in the act of book coveting. It was only natural. My mother taught school. My grandmother always made the children in the family discuss a topic over dinner, so we’d be able to express ourselves.

But, with few exceptions, public libraries were forbidden territory when I, Allegra Westbrooks, came to Charlotte in 1947 to head the Negro Library Services for the Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. At that time, Blacks had a branch on Brevard Street and a sub-branch in the Fairview Homes public housing project on Oaklawn Avenue. But, only whites could use the regular county library facilities. The old Cornelius branch was open then. I remember the striking feeling I had at the time when I could be shown the Cornelius branch, but I couldn’t use it, and that was the same feeling shared by the Black community. At the time, Blacks called the Main Library to request a book. They were told: “We’ll send it down to Brevard Street. You, as a citizen, can pick it up there.” The delivery service between the two libraries was provided by Ms. Westbrooks and the library’s chief janitor, who took the books when he went to stoke the furnace at the Brevard Street branch each morning, and, incidentally, after he left fixing the furnace, we the staff members kept the furnace going by putting in the coal and whatever was needed to keep the furnace running for the rest of the day. To help fill the literary void for Blacks in the county, I, Allegra Westbrooks, began placing books in churches for neighborhood use, because we had no branches in those communities. But, they weren’t quite satisfactory, because they were open only on Sundays. In the meantime, Allegra Westbrooks launched a campaign to attract people to the Brevard Street branch. The director told her: “Do what you can to make citizens use the Brevard Street branch. I don’t care if you have to have a tea party.” [interviewer laughter] Therefore, she had prominent people speak from the pulpits of Black churches, and she, herself spoke to sell the gospel of books and reading. She was visiting churches, going to clubs and organizations, and personally becoming part of the organizations themselves – the Girl Scouts, the YWCA, and so forth. In fact, we formed a coalition of people working in human services to strengthen what each of us was trying to do – to get the library used.

About Allegra Westbrooks

Allegra Westbrooks was born on March 13, 1921, in Cumberland, Maryland. She spent her formative years in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where her mother and grandmother raised her. Westbrooks graduated from E.E. Smith High School and attended Fayetteville State University, where she graduated valedictorian of her class in 1940.

She spent two years as a teacher in nearby Jacksonville, North Carolina, before attending Atlanta University’s School of Library Science. After graduating in 1945, Westbrooks briefly worked as a librarian in Louisville, Kentucky. In 1948, she was hired to head the Brevard Street Library in Charlotte and became the city’s first professionally trained African American librarian.

Westbrooks sought to increase the collection and circulation of African American authors and employed a Book-Mobile to help improve literacy among African American youth. She joined the local chapter of the NAACP, where she worked as a community coordinator. In 1957, Westbrooks was appointed Supervisor of Branches, becoming the first African American to work in a leadership role in the city’s main library. She would continue in similar leadership roles until 1984 when she retired. Westbrooks died in 2017.

Arthur Griffin Remembers Allegra Westbrooks

Arthur Griffin shares how Allegra Westbrooks pushed him to read.

Transcript: The public library, unfortunately was called the “colored library,” was on Brevard Street. So, with respect to trying to check out books – and my favorite lady, Ms. Allegra Westbrooks was a librarian, would always try to say: “Hey, Arthur, you need to get a gold star. You need to read these books.” So, I would walk from 6th Street over to Brevard Street to the colored library.